Recollections of the Past 30 years pursuing Coelacanths

Jerome Hamlin, creator dinofish.com

When we arrived in the Comoros with all out gear in late November 1987, we were not greeted by a red carpet, a flying carpet, or any carpet. After settling into the Ylang Ylang hotel with our equipment, we were all summoned to a ministers’ office and put through an interrogation right down to details of our housing, who was staying where, why had we reneged on a house rental arrangement, and so on. The minister was a hold over from a period when the Comoros briefly had a Marxist government. Our answers were innocent enough and we were free to go, but then I was approached by two members of the Ministry of Production. They politely wanted to know what the hell were we doing there trying to catch a coelacanth? I wondered what had happened to the support from the Comorian Ambassador to the US who had assured me we were all set? I was able to clear things up. We signed some kind of contract. Back in business. Welcome to expedition reality.

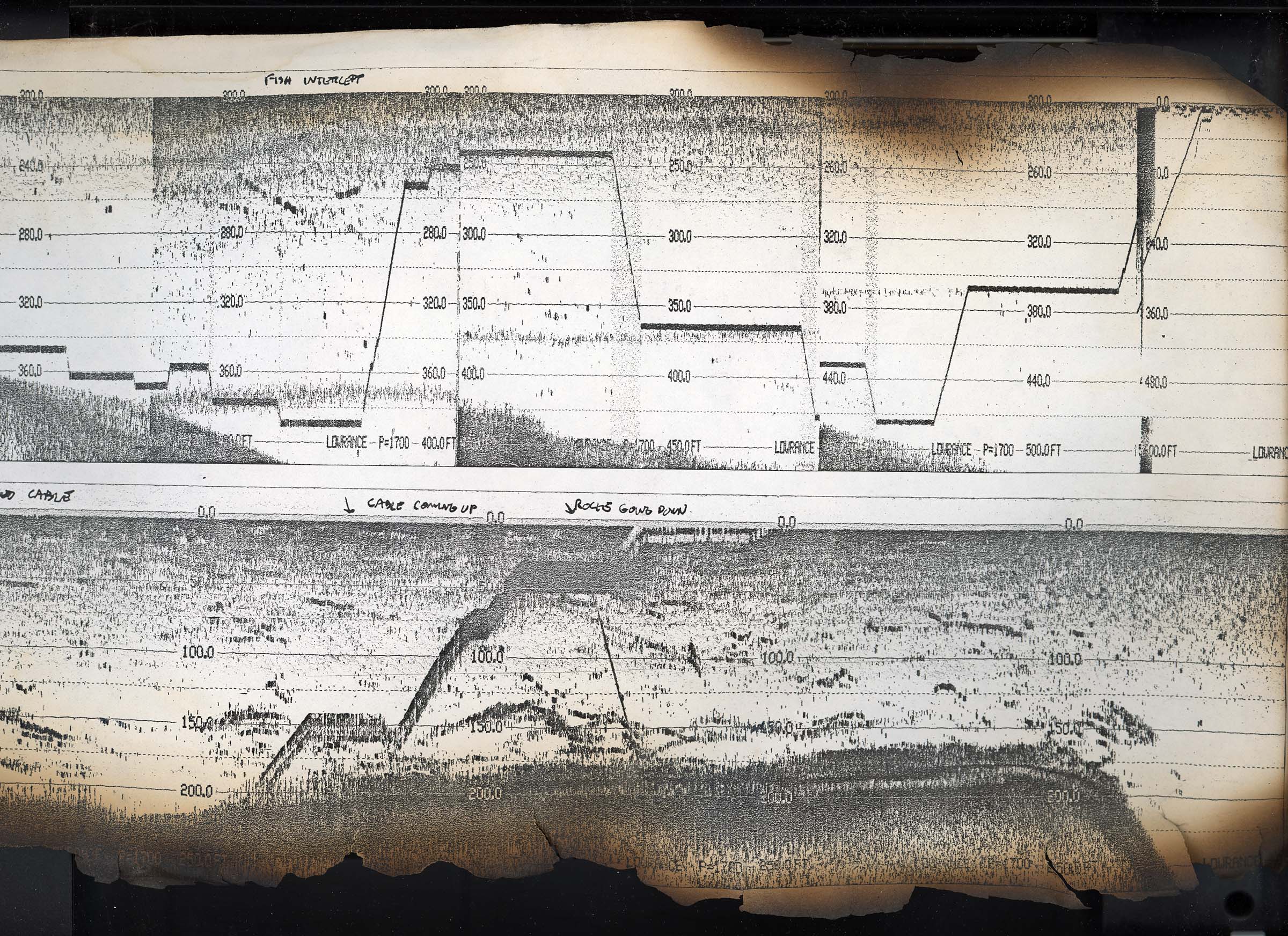

A section of Lowrance X-16 sonar roll graph (later damaged by a fire at the archive storage) shows rocks lowering a bait, the canon ball being raised, and (top), some fish signatures. Noise on the graph would make it difficult to detect an individual coelacanth.

We needed one or more boats for our operations. Two had been promised by the Comorian government back in NY, but now here in the Comoros, nothing. I had to start from scratch on this basic item and had a piece of good luck. A security guard at the Ylang Ylang struck up a conversation with me. His local name was "Mombasa," a huge Black man right out of a safari movie, and in fact he had been in one or two of the John Wayne masterpieces as an extra. (Most Comorians are descended from Arab or Persian traders and their coastal Bantu slaves producing an a distictive light coffee skin tone.) Mombasa would become our “fixer” a term I had never heard or understood before, but without support from above, he would be essential. Mombassa arranged for us to rent a “Japawa.” “Japawas” were open fiberglass fishing boats, about 30 ft. long, with diesel engines. They were part of a foreign aid package to the Comoros from Japan. At the same time, helpful American consulate mechanics prepared a mount for our Sonar transponders, that could be placed over and then removed from the gunnels of the boat. We were ready for our fist night of fishing.

A fisherman guided us to the "coelacanth fishing grounds,” which, it turned out, were none other than the usual fishing ground of the village of Iconi. Immediately, there were problems. It was very difficult for the Japawa to hold station in the brisk current. So we drifted one way as the canon ball fishing rig lagged out in another. Soon it was outside the sonar observation cone, so while I studied the bottom 700ft below on the sonar screen, the canon ball rig with bait attached was somewhere else. The sonar was able to pick up the bottom way below us, and when it was underneath, the canon ball. With an echo reflector attached just above it, the canon ball appeared as a dark splotch. Fish showed up as inverted V’s, but all fish looked the same. There was nothing to distinguish a coelacanth from a grouper or snapper. I was overly tech oriented, so I clung to the use of the sonar, while the others simply began fishing Comorian style, attaching a couple of rocks with a slip knot which was jerked free when the stones hit bottom, releasing the hook and bait. The problem with this approach was it gave us no advantage over any of the other fisherman out in the area at the same time. The technical edge of using the sonar had failed. A high power flashlight we brought for night operations fell overboard. I watched its light descending in bright circles as it dropped into the depths, carrying my hopes for a quick success with it.

Video Feature: Aquarium staff collected flashlight fish.

Exit video with back arrow.